Nothing golden can stay; nothing lasts forever. Or in this case, appreciation is fleeting these days.

I remember that until the internet became what it is now, people seemed easier to please. Either that, or people’s opinions morphed toward hatred. Critics will be critics, but the average moviegoer just seemed less picky.

|

Ghostbusters II was thoroughly enjoyed by everyone I knew. Nobody used to have a problem with any of the Back to the Future sequels, Return of the Jedi was very much beloved (comparisons to Empire be-damned), and the Batman movies (sans “that last one”) were all great. Oh, how times change. Now when you hit the net, if there aren’t complaints or hate thrown at Tim Burton’s Batman flicks, it seems not to be a Batman film discussion at all. One constant, however, is the hate of Joel Schumacher’s Batman films. Nolanites and Burtonites tend to agree with that one. “Nipples, Neon and Nincompoopery!” is what they cry.

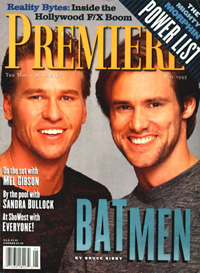

Going back to the previous train of thought, I want those of you who can to remember back to 1995. Uh-huh. Everyone loved Batman Forever. But the years haven’t been so kind to its legacy, and its sequel’s reception didn’t help things. Back in a time when a film’s entertainment value was what mattered most, Batman Forever rose to the top of the box office food-chain to dominate its year of release. Not to mention the merchandising, the McDonald’s tie-ins and the hit soundtrack album. Now, it’s a pop-culture footnote, quashed by the drabness of Christopher Nolan’s pseudo-thriller Batman films. While those films are to be lauded for their decision to be serious with the material, I remember when Batman wasn’t a tool for nerds to try to prove how sophisticated and deep they were for understanding the character. I remember a time when, much like the comic books that spawned him, he was a character of mystery and adventure. My personal preference is Tim Burton’s pair, but make no mistake: Joel Schumacher’s couple have a bum rap. And I’m going to unearth their hidden value.

Batman Forever: The Best One?

Let’s get the obvious out of the way. There are neon lights all over Gotham. Giant, improbable statues in every corner; and between Jim Carrey and Tommy Lee Jones, there was no scenery left undigested. But if you’re wise enough to look beyond dismissible trappings, you may find the richest character study of Bruce Wayne yet put to film, in a very hip movie. How’s that for subtext? While Tim Burton explored Batman’s psyche through the villains and how they compare to him, Schumacher goes for the hat-trick on his first outing: he questions Wayne’s very identity and reason for being. And he does that by calling back to Burton’s efforts (this is a sequel, after all).

Flashback: in the first film, Batman discovers the Joker murdered his parents, and suddenly he gets bloodthirsty (Check it; he doesn’t start killing until he makes this realization). He kills the bum, and everything’s right, right? Maybe not. In Batman Returns, he’s on a rampage, killing indiscriminately anyone who opposes him. When he sees himself reflected in the murderous vigilante Selina Kyle, he pulls back from the abyss, fighting with morality once more (instead of instant murder, he now warns Max Schrek “You’re going to jail”). Attempting to redeem Catwoman (and himself) from the darkness of their craft, Bruce is spurned by her and is left unfulfilled. Did Burton intend this character arc? Only he knows for sure. But what we do know is that Schumacher and his scriptwriters saw these elements and ran with them, because Batman’s conflict is at the heart of the film (even moreso fleshed-out in Forever’s deleted scenes). The previous two films’ arc for Bruce is made canon in his lecture about revenge to Dick Grayson in the film’s second act:

BRUCE

“Then, it will happen this way: you make the kill. But your pain doesn’t die with Harvey; it grows [Murdering the Joker in the first film]. So you run out into the night to find another face. And another, and another. Until one terrible morning, you wake up and realize that revenge has become your whole life [His rampage in Returns], and you won’t know why.”

Bruce speaks from experience to Dick because he’s been there, done that. In the film’s conclusion, Batman is finally able to make peace with himself over his murdering history by steering Dick Grayson off the path he himself took. He takes the temptation away from Grayson by killing Harvey himself; his hands already aren’t clean, and if he can save Dick from running too close to the abyss, he’ll kill one last time.

|

But that’s tying up the Burton arc. What does Schumacher bring new to the table in Forever? The central element of the film (which admittedly is lessened by portions being deleted) is Bruce’s inability to function properly as either Bruce Wayne or Batman. He doesn’t know who he really is, and his worries about Dick following in his footsteps worsen his psyche, along with his guilt over Harvey’s condition. The Riddler tests Bruce Wayne, while Two-Face tests Batman. To quote Batman Begins, he’s “lost inside that monster of [his].”

Brilliantly and without being overbearing, the film enriches Batman’s origin without becoming contrived. Bruce feels responsible for his parents’ deaths. Unfortunately deleted from the film is a scene that finds Bruce rediscovering his father’s journal, and reading the final entry; Bruce’s movie choice was not the one accepted that fateful night out. They all went out to see a movie of the parents’ desire, absolving Bruce of his guilt; he is able to become one with his destiny as Batman. Hence in the finale, Bruce explains to a defeated Riddler that he “had to save [Chase Meridian and Robin] both. You see, I’m both Bruce Wayne and Batman. Not because I have to be. Now, because I choose to be.” This coming after the excellent cliffhanger wherein he is forced to choose whom to save; Bruce’s girlfriend Chase, or Batman’s partner Robin. A choice between either identity. Thus, he is now Batman “Forever.” Clever!

“Okay,” you say, “they explored Bruce well. What else you got?” Plenty.

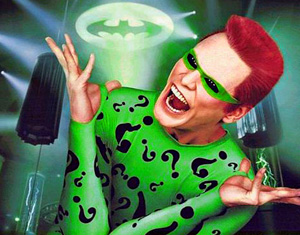

Although on the surface, Carrey’s Riddler and Jones’ Two-Face are overactive, if you really think about the severity of their actions and notice the undertones of menace, they are rather top-notch. Which is not to claim every moment of theirs is brilliant, but hey; Pobody’s Nerfect. Of particular note is Carrey’s Nygma, pre-Riddler. He manages to be a truly terrifying fanatic; obsessed with Bruce Wayne. Subtly, in the later half of the film at the Nygmatech party, he is trying to be an exact copy of Bruce out of jealousy. A brilliant touch that I hadn’t noticed until much later. Let’s face it, if you encountered Jim Carrey’s Riddler in reality, you’d be terrified. The guy is downright psychotic. So too is Two-Face.

Two-Face’s first scene is truly menacing. He’s a man of absolute unpredictability; his calm demeanor giving way to the frightening mania underneath. With Tommy Lee Jones, Harvey Dent and Two-Face are two souls in the same casket. His first lines in the film to his captive are the stuff the character is made out of:

TWO-FACE

“So you’re counting on the winged avenger to deliver you from evil, aren’t you my friend? Are you a gambling man? Well, what’s say we flip for it? One man is born a hero, his brother a coward. Babies starve, politicians grow fat, holy men are martyred and junkies grow legion. Why? LUCK! Blind, stupid, simple, clueless luck! A random toss: the only true justice. Let’s see what justice has in store for you!”

Even though he becomes rather loud and overbearing later on, there’s a constant undercurrent of manic intensity. Again: in reality, this guy would have you scared stiff. Both performances are as true to the comic book as it gets. The Riddler’s mania has been a staple since Frank Gorshin, and Two-Face’s obsession with dichotomy is spot-on.

So much else shines in the film. Val Kilmer is darkly mysterious and suitably fractured in his psyche. Next to Michael Keaton, he’s the best person for the Cape and Cowl. Nicole Kidman is great, aside from some dated pop-phychobabble. Michael Gough is solid as Alfred, as always. The film score is suitably dark when it needs to be. Elliot Goldenthal is no Danny Elfman, but who is? Goldenthal crafts a theme for Batman, that while not heroic or exciting, evokes a dark mood and an undercurrent of tragedy.

|

Chris O’Donnell brings an excellent sorrow to Dick Grayson, being another of the film’s highlights. The logic in making Robin start off in his late teens was a stroke of brilliance; not only to appeal to the prime target audience at the time, but also because it skirts the questions of Batman’s child endangerment. The death of Grayson’s family is another highlight. It’s beautifully portrayed. And in the same way as the Joker murdering Bruce’s parents in the 1989 original, Two-Face brutally murdering Dick’s family just because his coin tells him to just makes the package more awful; to think that their lives were worth no more to him than a random coin toss. Deplorable!

The gravity of the film’s challenge is also of note. The stakes are a good challenge, and are befitting of the Riddler. His plan to become the smartest man on the planet and ruin everyone’s minds in the interest of absolute knowledge is considerably twisted. And his discovery of Bruce’s identity and destruction of the Batcave is a shocker; never before has Batman been so completely vulnerable.

The action is exciting; the initial fight between Batman and Two-Face’s goons at the beginning of the film is the closest that Batman film action has ever come to matching the recent smash-hit “Batman: Arkham” video games, with their intense, calculated fighting style. And the effects still hold up without a hitch. Even the much-lambasted production design is like nothing seen anywhere else. And it’s definitely a good thing. Owing to the Batman design staple, the city is gothic and overwhelming; a place of overburdened souls.

Seal’s hit song “Kiss from a Rose” covers Chase Meridian’s salvation of Bruce’s psyche, comparing her love to a “kiss from a rose on the grave” of Bruce’s deadened soul.

I could go on and on about how great Batman Forever truly is, but I have to leave great things for you to discover on your own. Let’s move on to…

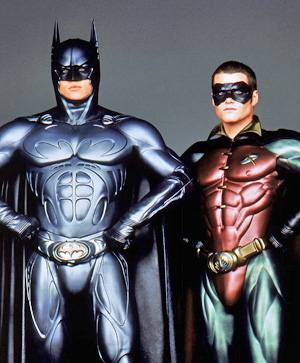

Batman & Robin: The Fun One

Remember that I said “Pobody’s Nerfect.” But perfection isn’t necessary. Thankfully, recent years have been kinder to this film. Since the franchise got back-on-track, most people look back at Batman & Robin and laugh. And why shouldn’t we? Most of it was intended to be funny. That’s right. You didn’t think Arnold’s ice puns were meant to be serious, did you?

|

Let’s be honest: there’s an inherent absurdity to Batman. I firmly believe that the more overtly serious or realistic you try to make Batman, the more you expose its silliness. Think about it. He’s a guy in a bat costume fighting crime and ridiculously themed villains, and this Bat-Man somehow scares criminals (no real crook would ever fear a guy in a bat costume, I’m sorry) and doesn’t get caught. And he seemingly can do anything. When we embrace that Batman may not be the most believeable concept, we thus can expand our mind not to shun a bold or fantastical idea. That’s what comic books are all about, folks.

The emotional core of Batman & Robin is the importance of family. How’s that for a curve-ball, eh? Mr. Freeze is trying to save his wife. Bruce is trying to save his surrogate father Alfred, while Dick is trying to find the acceptance of his surrogate father, Bruce. Barbara is trying to save her Uncle Alfred’s dignity, and Poison Ivy’s loyalty is to no human but instead her “babies;” her plants.

Not every aspect of the film is defendable, but there’s nothing that’s really that infuriating aside from the random butt-shots when the heroes suit-up (more comedy, I suppose). The plot with Alfred dying, and his scenes with Bruce in particular are some of the best scenes of any Batman film. Again, people who only notice that the film has “Nipples, Neon and Nincompoopery” were too busy hating to slow down and notice the film had more going on than its madcap antics.

George Clooney is greatly underrated for what he brings to this film. As Batman, he can be a bit blasé, but Bruce Wayne is where he really shines. And even as Batman, his protective relationship over the headstrong Robin is excellently fleshed-out. He’s no-nonsense with his sidekick, but not to denigrate him; he worries for him; but as Alfred says to him: “You must learn to trust him, for that is the nature of family.”

The film is fascinating in the fact that it actually evolves Batman further. As a result of his newfound inner-peace in Forever, Bruce is no longer morose. As in the Batman comics of the 1970s and early 1980s, Bruce continues his fight because it is his duty, but he has made peace with the loss of his parents and is able to function correctly as a human being. This is an excellent maturing of the character, and evolution of this sort should always be welcomed.

The film even bravely points out the inherent futility of Batman’s agenda. During a moment in which Bruce feels uneasy due to his bickering with Robin, he converses with Alfred:

BRUCE

“Alfred, am I pig-headed? Is it always ‘my way or the highway?’”AFLRED

“Yes, actually. Death and chance stole your parents. But rather than become a victim, you have done everything in your power to control the fates. For what is Batman if not an effort to master the chaos that sweeps our world? An attempt to control death itself.”Bruce looks away to the window and recalls putting flowers at his parents’ gravestone.

BRUCE

“But I can’t, can I?”ALFRED

“None of us can.”

That, my friends, is some heavy stuff. It’s not many comic book films that are bold enough to explore the character’s weaknesses, much less have the hero himself come to realize them. Recalling this chat, later on in the film as Alfred lay dying, Bruce visits him for what will be the last time, before he steps out to handle his dual responsibilities. At this point in the film, Alfred will surely be dead by the time he returns.

BRUCE

“I spent my entire life trying to beat back death. Everything I’ve done, everything I’m capable of doing… but I can’t save you.”ALFRED

“There is no defeat in death, Master Bruce. Victory comes in defending what we know is right while we still live.”BRUCE

“I love you, old man."

Holding back tears, Bruce moves closer and gives Alfred a kiss goodbye. It’s a truly crushing scene, performed brilliantly by both Clooney and Michael Gough. This film best explores the relationship with Bruce and Alfred, even farther than many of the comic’s storylines have done.

And when you keep this in mind, the film from then on has an additional layer: Bruce has to go out and fight to save the city from becoming an icy graveyard while his second father lies at home, dying. And Bruce can’t be at his side. Heavy stuff indeed.

“All right, already!” You cry. “Family! This film’s deeper than I thought. Anything else?”

Poison Ivy is spot-on, right down to her costume. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Mr. Freeze is a delight. In his serious moments, he is actually rather good; but when he’s supposed to be funny, oh man, Arnold goes whole instead of going home. Ice puns are nothing new to the character. Even the beloved Animated Series episode “Heart of Ice” features cold puns. While the film may overdo them, the fact remains that they are a staple of the character. His make-up and costume, also, are to be revered. Arnold looks spectacular! Also, Dick’s quandaries with Bruce are lifted right out of the comic books.

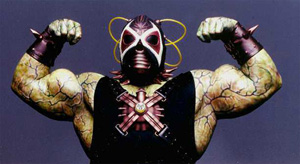

While Alicia Silverstone’s useless Batgirl is undefendable, Bane is craptacular! Don’t get me wrong; he’s poorly translated from the books (almost the polar opposite), but at least his moronic behavior is comedy gold. And he resembles the character, to-boot. Take that, Tom Hardy!

|

There’s so much more to cover, but as I said, I have to leave you some things to discover. Concluding, it’s like this: should the films have been more overtly serious without any comedic overtones? Absolutely. But are they devoid of any merit, artistic or adaptation-wise? Not at all. Whereas the 1960s Batman television series was campy and without any depth, Schumacher’s films are not that. They contain humor, but they themselves are not comedies.

People these days seem unable to distinguish humor from camp. Particularly in the wake of Christopher Nolan’s overbearingly drab Batman series, people have forgotten that the comic book character (even today) still deals with larger-than-life situations and fights against an array of colorful, unreal enemies. Ever since the Joker burst onto the scene in 1940, Batman has been a romanticized, adventurous crusader in outrageous situations. Outrageous, larger-than-life things are not inherently “silly,” like many Batman fans now perceive. And even if they were, would they be any sillier than the premise of Batman to begin with?

Do yourself a favor. Sit down with Schumacher’s two movies and a bucket of popcorn. Leave your cynicism checked at the door, and really, truly watch them. Pay attention to the performances, the nuance, and the plot. A Batman film doesn’t have to be watered-down to be great, nor does it have to have lengthy exposition to actually be deep. If you can ignore your desire to obsess on the Nipples and the Neon, you’ll find two adventures worthy of the Batman title. They may not be perfect, but in a perfect world, Bruce Wayne would have been a happy, well-adjusted guy.

And where would the fun be in that?

comments powered by Disqus

by Silver Nemesis

by Silver Nemesis

by Silver Nemesis

by The Joker

by The Joker

by The Joker

by The Joker

by The Dark Knight

by Silver Nemesis

by The Dark Knight